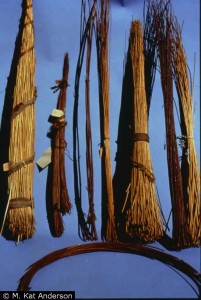

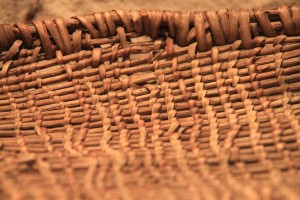

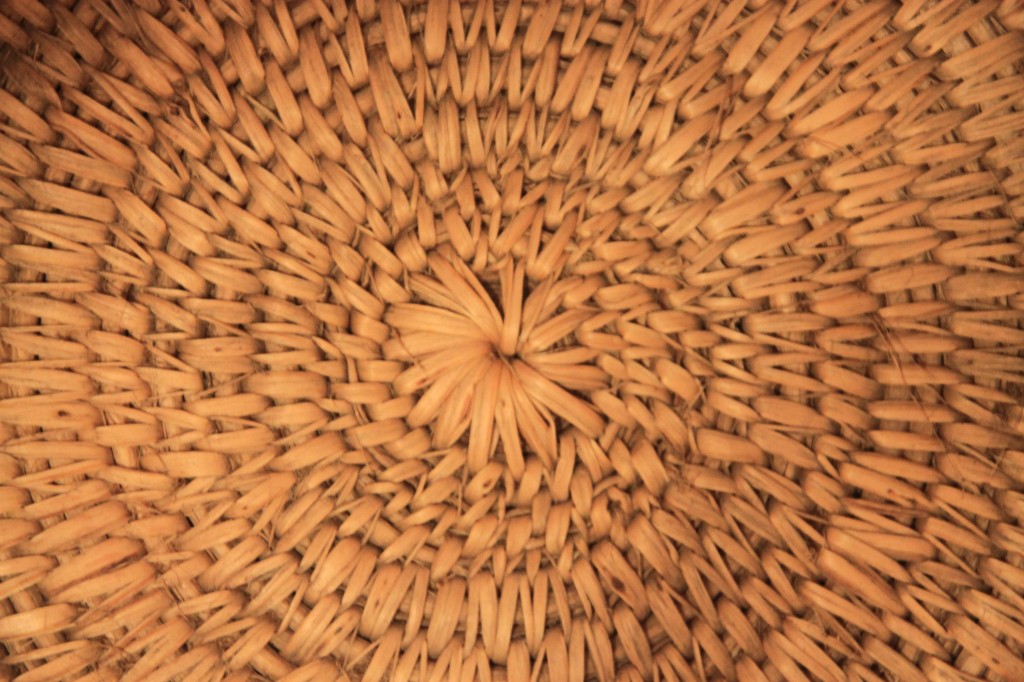

Due to vast amount of natural resources, Idaho has for centuries contributed to the extensive array of basketry in this country. From the Nomadic populations of the Nez Perce, Shoshone and many other Great Basin Tribes to the implantation of Rwandan refugees in the 2000’s, Idaho has produced a beautiful collection of woven artifacts. These pieces have for centuries been created by women who worked tirelessly to supplement their communal existence. Early Native American women fabricated massive jugs out of Idaho’s native Willow trees in order to help carry water to the tribe. Later Shoshone women would use the same tree to make seed baskets and beaters used to harvest and grind up mill for consumption. During the time of Lewis and Clark in the early nineteenth-century, Idaho’s native women continued to use their ancestors weaving techniques but their newly sedentary lifestyle allowed them to create pieces that were primarily seen as art. Nez Perce hats woven with bear grass adorned both men and women’s heads and were used in ceremonial events. Around the same time, intricately designed baskets served as vital trade currencies between the Native populations and the advancing settlers. Women would work in large groups to create hundreds of baskets the men would use as bargaining items with the white explorers. Women in Idaho continue to use the resources both natural and man-made to create baskets that help them assist their families and communities. Today women like Venantia Mukangeruka, a Rwandan refugee, who makes baskets out of grocery bags, uses age old techniques that once helped her nomadic ancestors and now helps her support her growing Idaho family. Since before Idaho was a state, women living in this area have been an integral part of the world of basketry and it seems the state will continue to showcase the diverse talents of Idaho women for decades to come.

Photo Courtesy of Idaho State Historical Society: 1962.208.4