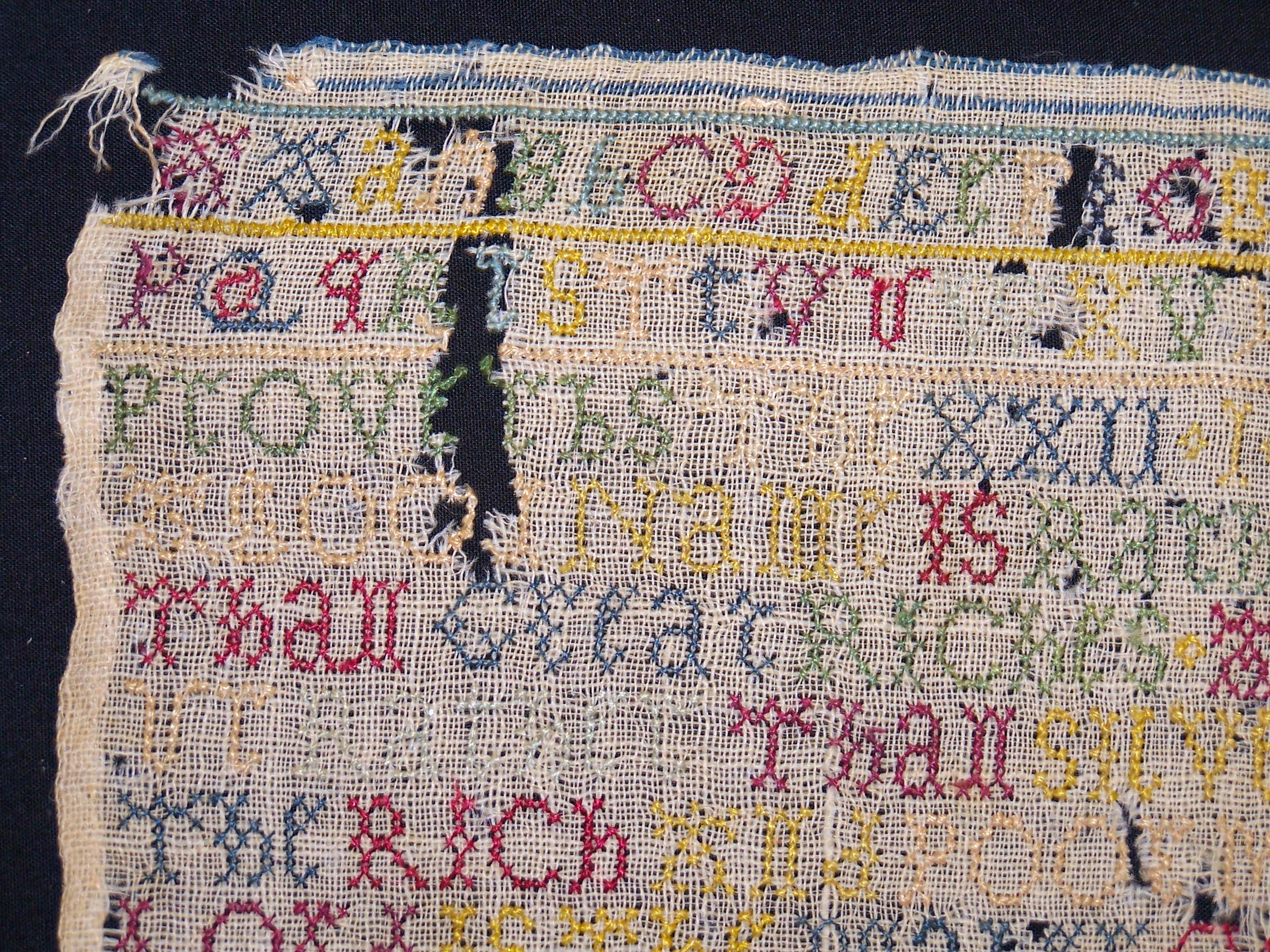

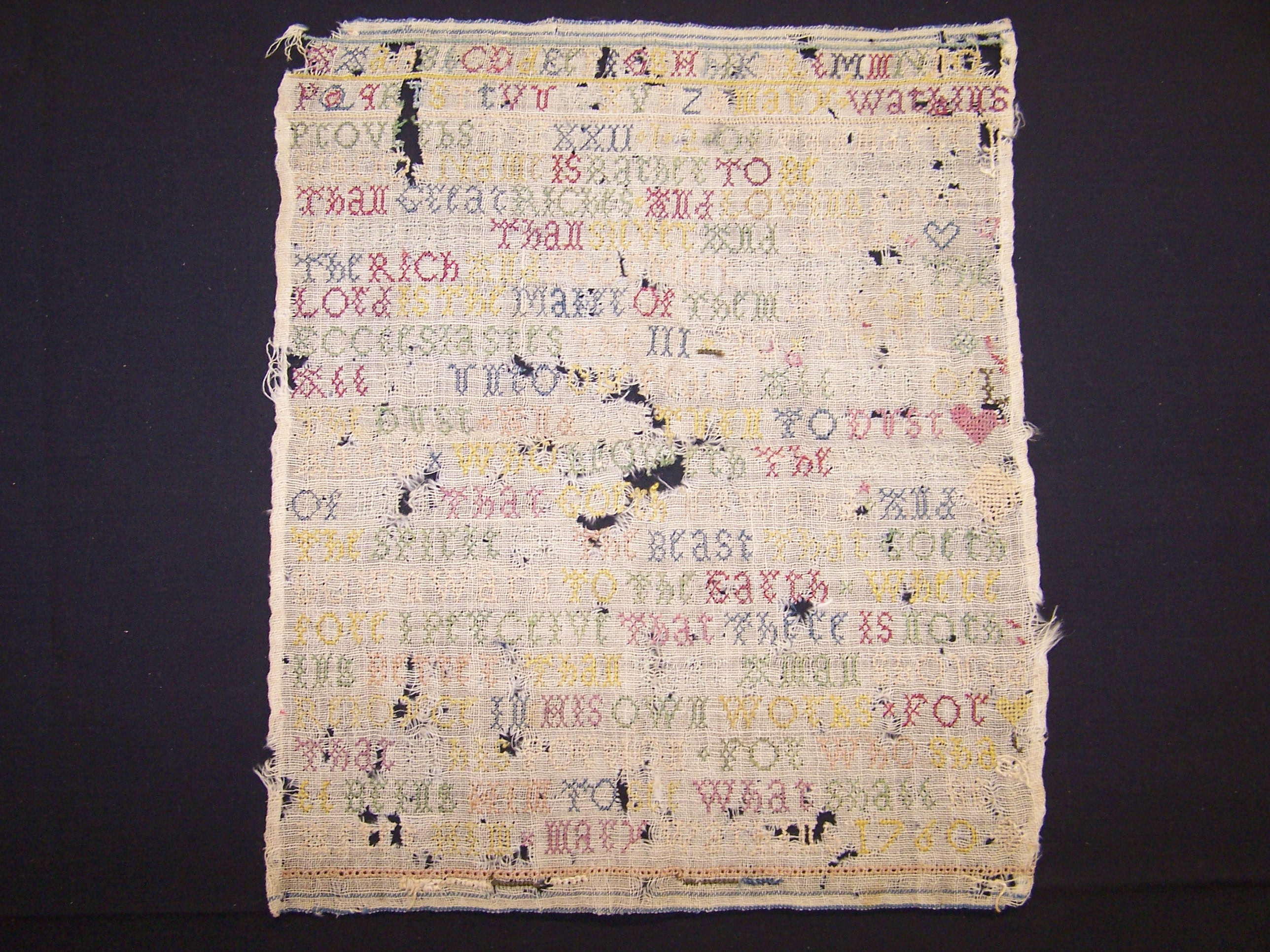

A Sampler made by Mary Watkins in 1760 in Shennington, England. The sampler was held on to until her great-great granddaughter, which was donated to the Idaho State Historical Museum. This particular sampler displays Proverbs and Ecclesiastes verses. Idaho State Historical Society, 1921.27.15.

Needlework Today

If you talk to your grandmother, chances are she has done or still does needlework at some point in her life. If you talk to your mother, chances are she has done needlework at some point in her life. However, if you ask yourself or your sister or even some of your friends, chances are you have only seen needlework at some point in you life. Needlework is no longer a regularly practiced form of art for the typical modern woman. As women enter the workforce and invention of the sewing machines, needlework has slowly began to die out.

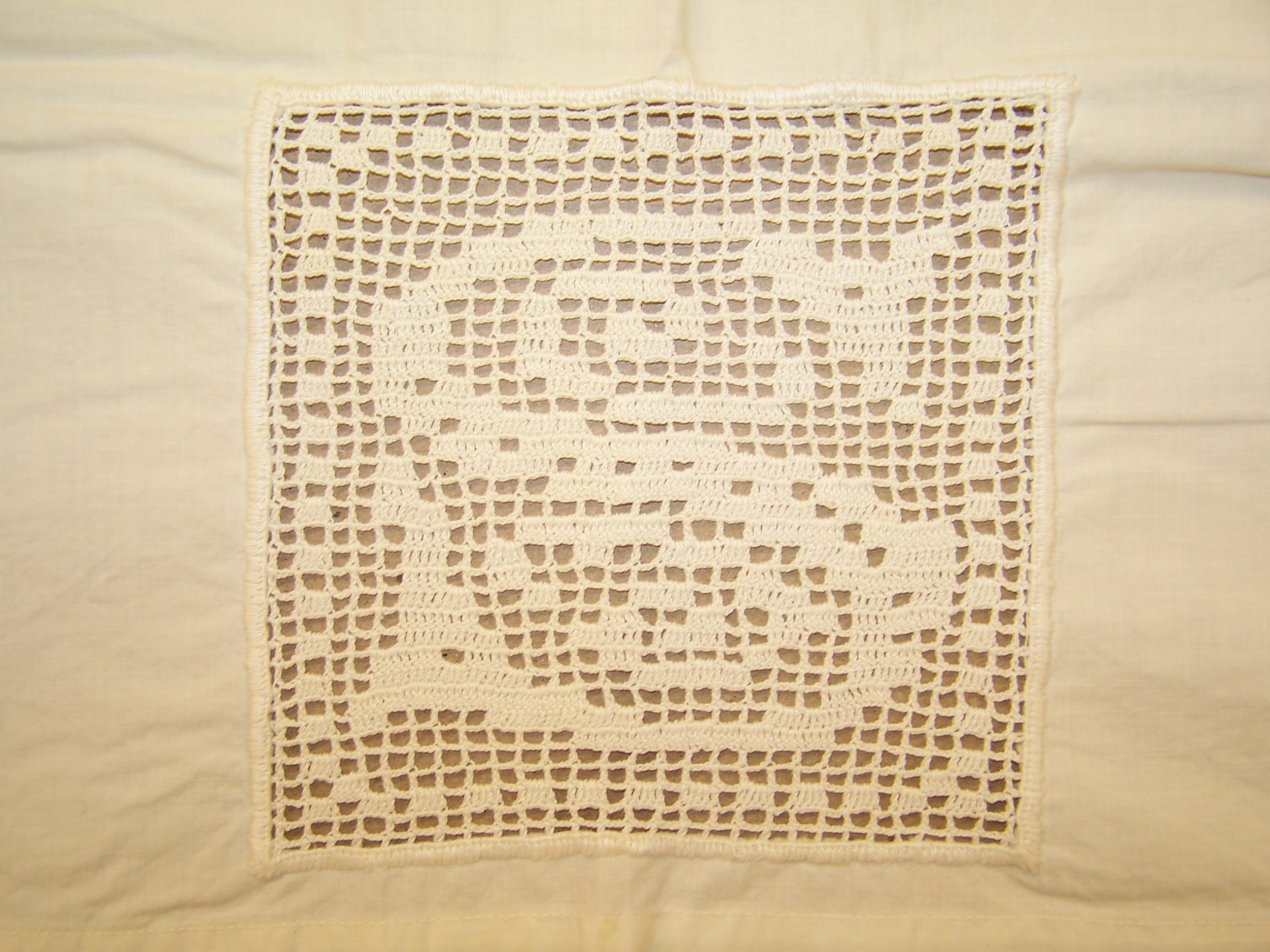

Embroidery is no longer in fashion; however, if you do want something embroidered all you have to do is program your sewing machine or take it to a seamstress and have it embroidered for a few dollars per letter. Needlework has also become an expensive form of art. For a woman that does practice needlework these day, it is not typical to develop your own designs; however, you go online and purchase a pattern for a fairly hefty expense and that is only for the pattern, not the materials you will need to complete the project. There are still a select few women that continue to practice needlework despite the advances in the sewing machine. (see Fig. 1) This can also be seen with Idaho local Cynthia Pease Mann’s needlework design. (see Fig. 17, 7 & 8)

The Culture Behind Needlework

The history and culture of needlework is one of the most fascinating, yet almost untold through the ages. The earliest examples of needlework show that “Ancient wall paintings and sculptures show that embroidery was worked on clothing from the earliest times.” (1) The earliest known fibers for thread was probably “made from intertwined stems and grasses, until a way of twisting short fibers and animal hairs into continuous strands evolved about 10,000 BC.” (2) Sewn objects have been found as early as 5000 B.C that were in tombs of ancient South American and also Egyptian rulers. Needlework was done all over the world and on all continents. It seems that almost all indigenous peoples have done needlework in one form or another. Blackwork, an interesting form of needlework “ featured geometric designs on white linen, using the wool from black sheep, and it is believed to have been brought to England in the sixteenth century by Catherine of Aragon, the Spanish first wife of Henry VIII.” (3) The earliest sampler still in existence “was stitched by an English girl, Jane Bostocke, in 1598 – just over 400 years ago.” (4) In this exhibits the oldest example of needlework is a sampler created in 1720. (see Fig. 1)

There were many different cultures that are represented by needlework. India, Asia, Europe and most of the world has its own forms and patterns that different cultures have developed. There are designs and patterns that are linked to families and the ways that they lived, worshiped and did the everyday ways of life. To some cultures, needlework brings a rich woven history that can be handed down from generation to generation. With these patterns and schemes, “designs for embroidery came with the traders, first from the Portuguese, then Dutch, and finally the English setting off on long voyages to bring back cargoes of all sorts, especially spices and textiles.” (5) Many cultures developed customs were passed down from generation to generation and these traditions still live on in today’s modern world.

American Needlework

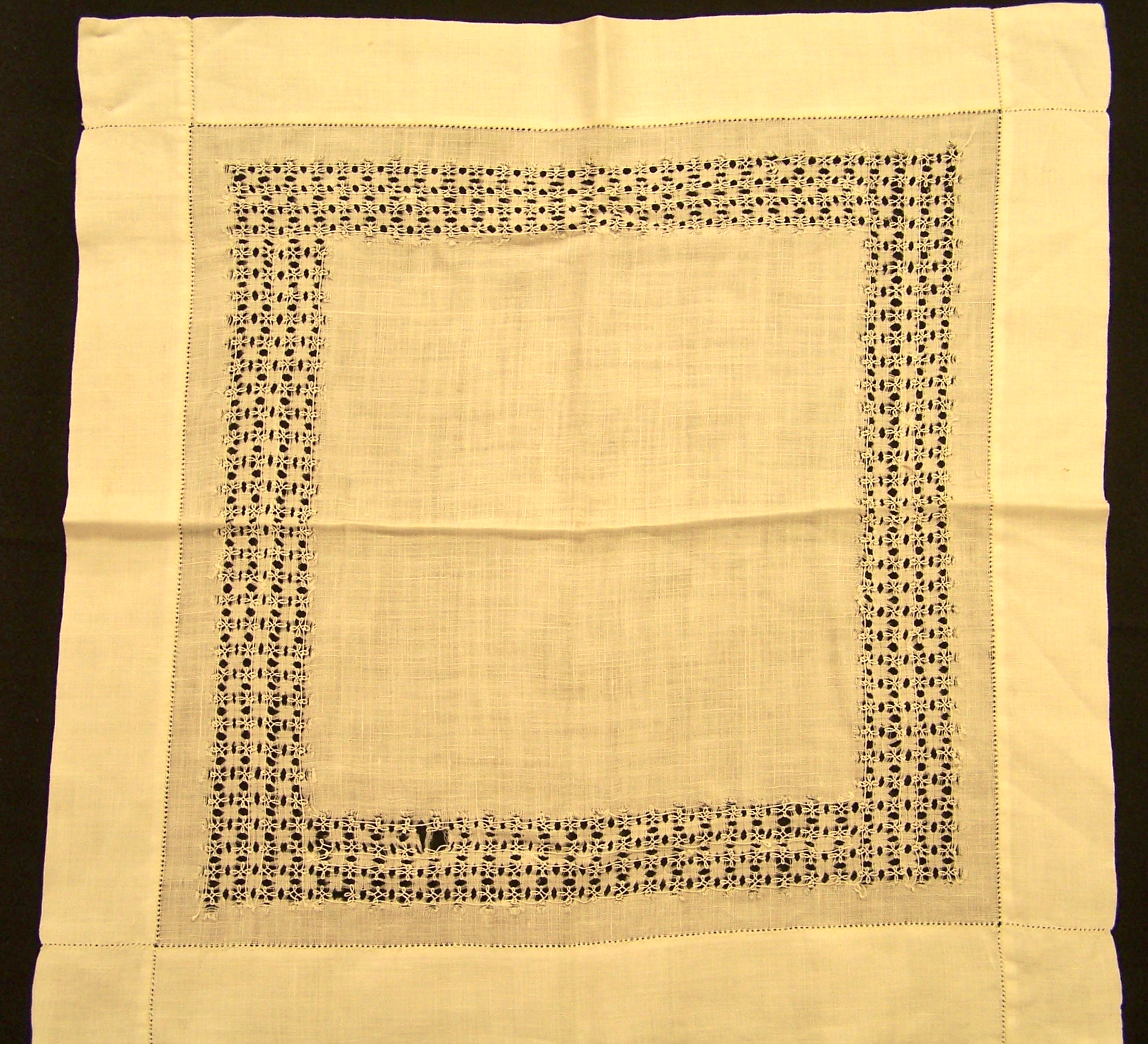

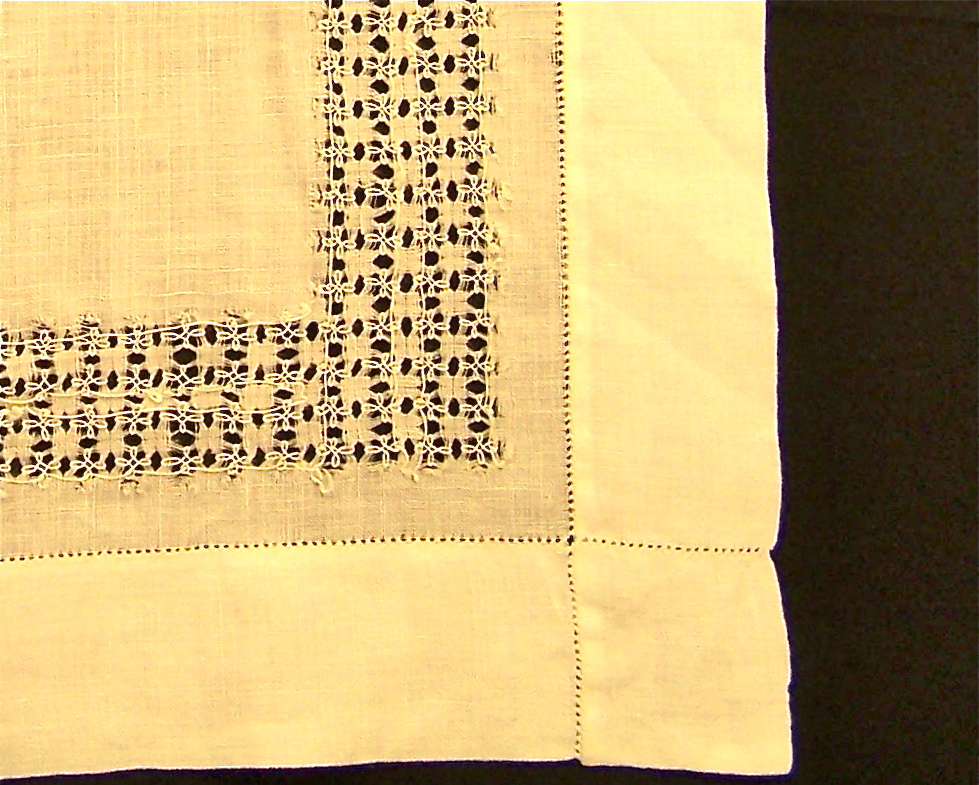

Needlework was brought to America over 300 years ago from Europe. (6) The needlework brought from Europe was considered very formal and as Rose Wilder Lane argues in her book, Book of American Needlework, “In typical Old World needlework, each detail is a particle of the whole; no part of the design can stand alone. The background is solid, the pattern is formal, and a border encloses all.” (7) American women thought differently about their needlework and change the Old World expectations immediately. However, you can still see various forms English style needlework in America. See these handkerchiefs as an example of American needlework resembling the styles of the Old World. (see Fig. 5 & 6) Lane talks about how American women took the Old World version of needlework and added the American spirit. Lane states, “They changed it, combined its symbols, gave it space and freedom and energy; and they created a new folk art: American needlework. (8)

Needlework covers a wide range of arts and crafts and is essentially, anything created with a needle; embroidery, crewel work, cross-stitch, needlepoint, patchwork, appliqué, quilting, hooking, crochet, knitting, weaving, candelwicking, and even rugmaking. Only one of these forms of needlework is entirely American – pieced patchwork, however, patchwork was always a task for the poor versus an art. (9) The poor would use whatever pieces of fabric they could find to make anything they needed. One of the most famous pieces of American patchwork is our very own star spangled banner created by Betsy Ross in 1776. (10) A pillowcase made by a wife to her husband who was at war illustrates some of the fun character brought to needlework by women in Idaho. (see Fig. 11 & 12) In today’s world it is not likely a woman would make her husband an embroidered pillowcase to take to war. It is more likely she would create a photo book or a scrapbook for him to take as a memento of his family.

Needlework Tools

It is interesting all the tools and accessories used to help produce needlework pieces. Moreover, tools and accessories have changed over time and are intertwined with changing social and economic times. These changes have affected many various forms of needlework tools. E. Johnson describes the long history of needlework dating back to Roman times and innovations that led to changes throughout needlework. Johnson gives examples of various tools used for needlework from thorns, fish bones, carved bones and ivory. For those who could afford it, different metal compounds were used for needles. (11) There were also various needle casings, ranging from very elaborate to ordinary wood or cloth cases.

Johnson also shows very intricate thimbles, thimble cases and workboxes. Thimbles were used because the immense constant pressure of pushing in the needle and stopping the needle. Traditional thimbles were made out of metal (12)—Johnson shows that collectors have found thimbles from ivory, wood, plastics, rubbers, glass, and porcelain—if you own thimbles, you would also need thimble cases that vary in size and detail. (13) The metals used vary from aluminum, silver, brass, and nickel. (14) Women would have also used scissors to cut the material and thread used for needlework. Johnson shows various types of scissors from large to very small and illustrates how portable scissors became. (15)

Thread is one of the important pieces to needlework because the thread was the outward appearance of what design was being displayed. As seen in most of needlework samples, thread was used for an outer-dimensional texture and decoration. (see Fig. 1-16) If a person had a little bit more money, they had many more kinds of thread that were made of various materials. Johnson shows some workboxes (16) and reel stands for thread. (17) These stands helped to keep from thread getting tangled. Some workboxes were big enough to hold most tools. Johnson mentions that tape measures (18) and gauges were used to keep track of rudimentary style throughout a piece of work. Measuring tapes are my favorite tools because they are of different figurines that I have never seen before. To keep work intact to material or on a loom, clamps were used to keep material stretched. (19) According to Johnson, there was also darning and mending apparatuses used while making needlework and after completion to fix any irregularities there may be.

Fabric and Material

In the history of needlework it is important to know that the fabric used has a unique past of its own. According to D. Ayres, T. Hansen, T. McPherson, and B. McPhersonearly (20), early American needlework has used fabric like linen, cotton, silk and rayon. Those fabrics listed were the most common. These fibers may have traveled across the seas before being crafted into anything special. Different fabrics would be used for different crafted articles.

Cotton was the main fiber produced in America as seen in various needlework samples. (see Fig. 1-4, 9-16) Cotton was primarily used to make clothing. Linen was a hard and long process to make and came from the flax plant. Some of the flax plant was grown in America but most came imported from Europe (21). One of our needlework samples, the background was made out of cardboard and needlework stitched into the cardboard. (see Fig. 5 & 6) Crash was a fabric used for pillows and table linens. Silk was not grown very much in America and that fiber had to also be imported from far east and generally was traded for from American tobacco crops. The silk imported was used for finer things such as curtains and nice apparel, making it a very expensive product to use due to its rarity and expensive price. Silk has its weakness and deteriorates easily from sunlight. Due to the high price of silk, artificial fibers would be produced and finds its way into an affordable option to produce some crafted pieces. (22)

Most of the fabrics were combined to form an individual piece of work. It is very common to find combinations like linen and silk, or cotton and silk combined. While examining needlework of our past, it is good to know the fabric type and its origin as this adds to the meaning of the piece and its craft history as an art.

Stitching Patterns

Samplers are a group of letters, words, and simple objects. Samplers are used as either an example for someone or a way for a beginning needle worker to practice replicating letters, words, and simple objects. Samplers were often practiced on linen, wool or sometimes satin. Short bands of text or objects were used early on but the old format of a large number of short bands was replaced by wider ones of increased interest, more like pictures, and by the middle of the century borders are seen around a panel containing lettering, texts, biblical verses, and motifs. (23) American girls were expected to do two sorts of samplers. First, a plain sampler was used with the alphabet and numbers. The second sampler was more decorative sampler showing their expertise. Some larger samplers could be made up to 30 inches wide and divided into sections with texts, patterns and animals. (24) Samplers not only taught sewing but also taught a young woman the alphabet and numbers in her own language as well as, other languages and scripts. Several different types of samplers could be combined onto one sampler.

The Dictionary of Needlework lists thousands of different kinds of stitches on hundreds of different kinds of material. (25) The most popular being cross and tent stitching, although the more traditional Victorian and random long are also seen in the present. The Hardanger stitch as seen on the lace doily, (Fig. 5) is based on groups of satin stitches called the Kloster blocks. You must complete all of a Kloster block embroidery before cutting out the centers. Then you can add other decorative stitches to embellish see this website for examples. (www.embrodiery-methods.com)

The Future of Needlework

Rose Lane conveys her feelings regarding the meaning of needlework:

Needlework is the art that tells the truth about the real life of people in their time and place. The great arts, music, sculpture, painting, literature, are work of a few unique persons whom lesser men emulate, often for generations. Needlework is anonymous; the people create it. Each piece is the work of a woman who is thinking only of making for her child, her friend, her home or herself a bit of beauty that pleases her.

So her needlework expresses what she is, more clearly than her handwriting does. It expresses everything that makes her an individual unlike any other person – her character, her mind and her spirit, her experience in living. It expresses, too, her country’s history and culture, the traditions, the philosophy, the ways of living that she takes for granted. (25)

The history behind needlework is undeniable; however, the future is yet to be seen. Will needlework die out or will it last the test of time? The the sewing machine has made it easier, faster, and more accessible to create a quick intricate pattern on just about any type of cloth. The constant pull on a woman’s time allows for little spare time for art, never the less, a dying art such as needlework. This form of art has become less and less desirable as the fashions have changed, cost has risen for quality patters, and the cost for mass produced items is much less than making your own clothing and designs. Needlework is hanging on by a thread but you never know what the future holds. If fashion trends change and women decide this form of art is worth keeping we may see needlework continue to develop throughout time.

View the needlework sample artifacts.

Endnotes

1. “History,” Classic Cross Stitch, accessed April 11, 2012, http://www.classiccrossstitch.com/history.html.

2. Ibid.

3. Ibid.

4. Ibid.

5. Ibid.

6.Rose Wilder Lane, Book of American Needlework, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963), 64.

7. Ibid., 12 .

8. Ibid., 14.

9. Ibid., 14.

10. Ibid., 15.

11.Eleanor Johnson, Needlework and Embroidery Tools (Prince Risborough: Shire Publications, 1999), 37.

12. Ibid, 14.

13. Ibid, 15.

14. Ibid, 14-16.

15. Ibid, 4, 6-7, 9 & 29.

16. Ibid, 5.

17. Ibid, 27.

18. Ibid, 24-25.

19. Ibid, 12.

20. Dianne Ayres et al., American Arts and Crafts Textiles (New York: Harry N Abrams, Inc., 2002).

21. Ibid.

22. Ibid.

23. Lanto Synge, Art of Embroidery: History of Style and Technique (Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club , 2001), 203.

24. Ibid., 204.

25. Rose Wilder Lane, Book of American Needlework, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963), 13.

References

Ayres, Dianne, Timothy Hansen, Beth McPherson, and Tommy McPherson II. American Arts and Crafts Textiles. New York: Harry N Abrams, Inc., 2002.

Eleanor Johnson, Needlework and embroidery tools. (Prince Risborough, Buckinghamshire: Shire Publications, 1999), 37.

“History.” Classic Cross Stitch. Accessed April 11, 2012. http://www.classiccrossstitch.com/history.html.

Lane, Rose Wilder. Woman’s Day: Book of American Needlework. New York: Simon and Schuster, 1963.

Synge, Lanto. Art of Embroidery: History of Style and Technique. Woodbridge: Antique Collectors’ Club , 2001.