The Evolution of Taxidermy through the Deconstruction of Fixed Gender Norms in the West

Philip Browning, Briana Cornwall, Sarah McIsaac, Jolee Thomsen, Rachel Van Note

An Introduction to the Practice

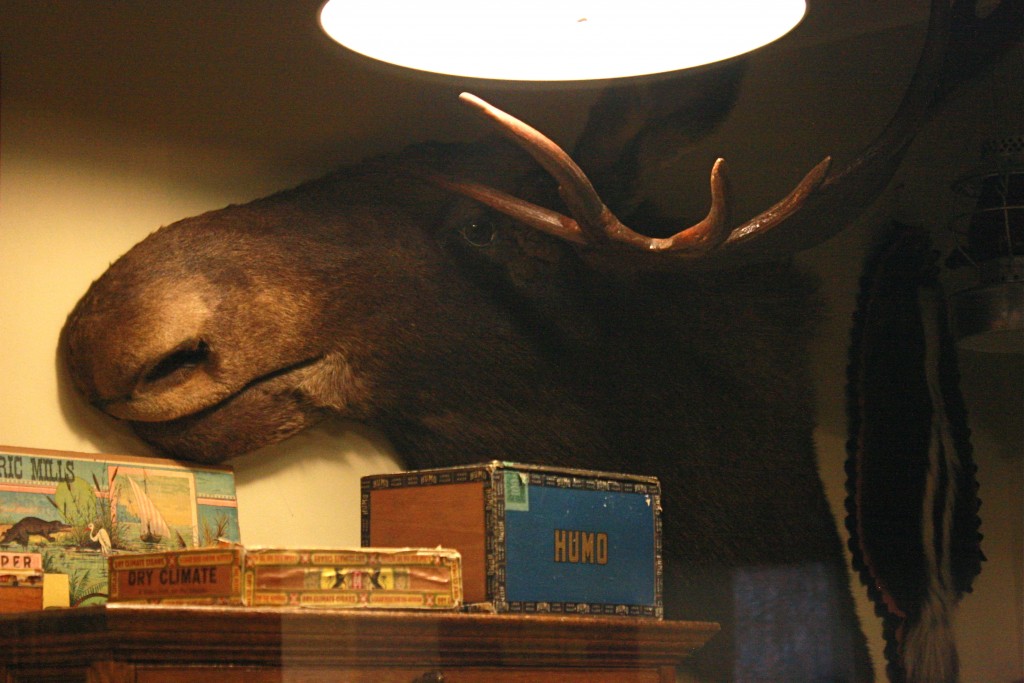

Taxidermy, the act of preserving and mounting dead animals for the purpose of display, has been practiced by humans for thousands of years—ancient Egyptians notably mummified remains of animals and pets, and even today in Idaho, the sight of the head of large game in a home or public establishment is not uncommon. (1) Figures 1 and 2 depict an example of what this might look like in a saloon. This piece was created circa 1942.

Figure 1 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society

Figure 2 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society

Modern reasons for practicing taxidermy vary, from displaying the trophy of a hunt, to representing the places a person has traveled, to preserving oddities, (2) like the two-headed calf in figures 3 and 4–this piece was presented to the Idaho Historical Society by G.L. Benrose and was mounted by E.H. McNichols of Star, ID.

Figure 3 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society

Figure 4 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society

The gender of those who practice taxidermy has similarly changed over time. Specifically, in the United States, expansion into the West in the 19th century helped fuel the evolution of taxidermy from a traditionally male-dominated field to a source of empowerment and high-skill employment for women. Westward expansion directly impacted the practice of taxidermy’s ushering in of women, as women in the West had more opportunity to challenge gender roles in their hobbies and occupations as the relatively unstructured frontier provided the physical space and sociological environment for the deconstruction of gender roles.

Although popular culture and textbook history typically only provides us with the names and personas of 1800s male adventurers, historian Karen Jones informs that “the allure of the West and its associations with adventuring, strenuous activity and escapism held appeal for some women as well as men.” (3) Women, too, had a love for adventure, and “transcendence of the boundaries of conventional female behavior [ . . . ] could be found among many female hunter travelers of the 1800s.” (4) As hunting is usually the first step toward mounting an animal, men have historically been considered the producers of taxidermy pieces. But if women did indeed break gender norms typically associated with the western frontier, they were certainly also performers of taxidermy. Westward expansion “promised adventure, interaction with nature and settler culture, and a route towards independence, belonging and empowerment,” (5) and opened venues for practicing work usually associated with men. Women today similarly identify with practices typical of male settlers in the West–Figure 5 shows a woman proudly holding her child up to a bear she has preserved and staged.

Figure 5 Image Courtesy of Anne Vinnola and Colorado Institute of Taxidermy Training

Who Performs Taxidermy?

By the mid-1800’s women were becoming more involved in hunting, particularly in the western states. Martha Maxwell, a Pennsylvania-born mother and wife, had always taken an interest in collecting and preparing animals killed by the male hunters around her. (6) As was the case for many women during this time period, moving out west with her husband provided her the opportunity to spend time in the mountains harvesting her own animals. She, and other women, hunted from the homestead and “transgressed gender codes” (7) not only for daily subsistence, but for pleasure as well. Taxidermy was Maxwell’s passion and by 1868 she had accumulated 600 specimens–from fowl to large game such as moose–and entered them into the Third Annual Exposition of the Colorado Agricultural Society. (8) From here she gained notoriety for her artistic talent and became known as one of the first female taxidermists. Figures 6 and 7 display a moose mounted by Ann Sherwood (circa 1919), a female taxidermist who learned to stage animals from her husband.

Figure 6 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society

Figure 7 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society

Why more information about women in the west performing taxidermy is not easily accessible raises some interesting implications—Maxwell could not have been the only woman transcending the roles assumed to be inherent to them. This lack of information might be attributed to the overlooking of women who do not fit into the categories provided by society. Regardless, the West was certainly a less stringent playing field for women in the 19th century, and women have since secured their place as taxidermists.

Within the past decade there has been a significant increase of women becoming actively involved in taxidermy and in many cases becoming professional taxidermists and successfully entering, competing, and redefining the taxidermy profession. Traditionally male-dominated practices, like hunting, fishing, and taxidermy—which have historically been considered as taboo, rough, and uncharacteristic of women—have been taken up by women. (9)(10) Today women enjoy these activities, some alongside their male counterparts, and they are surely succeeding.

A contemporary example of women in taxidermy is Anne Vinnola. Vinnola alongside her husband owns and teaches at the Colorado Institute of Taxidermy Training. She also owns the Big Timber South Taxidermy Studio located in Canon City, Colorado. (11) Vinnola’s institute has educated and certified more than one thousand students as professional taxidermists and many of her students are women. (12)

Her and her husband’s business has mounted all different types of game. Everything from waterfowl, fish, birds, small, and large game, Vinnola has expertly staged in her studio. (13) Her credentials are extensive. In addition to her taxidermy success she publishes a daily blog called “Team Huntress: Empowering Women Outdoors,” she is a member of the Professional Outdoor Media Association, life member of Safari Club International, National Rifle Association, sponsor of the Friends of NRA, National Shooting Sports Foundation, and Woman’s Outdoor Media Association. (14)

Vinnola has created her own success with her taxidermy business and school. Other women have become actively competitive with their taxidermy by entering examples of their work in judged competition. (15) An example of a successful competitive woman taxidermist is Alicia Love. (16)

Love is a professional taxidermist. She competes in large events and has won several including the Best of Show at the National Wild Turkey Federation’s “Grand National Wild Turkey and White-Tailed Deer Taxidermy Competition” in South Carolina. Her entry in the wild turkey category stunned the judges and earned her top marks along with a nice cash prize. (17) Love’s craftsmanship is just one example that many individual women create.

Today, women’s attention to detail is providing an excellent competitive advantage. Fish and bird specimens require more attention to detail than other game specimens. Women such as Anne Vinnola and Alicia Love are helping to solidify women’s place in the taxidermy profession. The taboo is fading from taxidermy’s gendered tradition and women are providing valuable educational opportunities for other women and exemplifying themselves as professional taxidermists.

How Does One Perform Taxidermy?

Just as any traditional form of art does, taxidermy has very specific parameters for what is considered “good” or “bad” work. According to Charles Waterton in “On Preserving Birds for Cabinets of Natural History,” “any common clown can stuff a bird.” (18) He mentions that all too often animals are over-stretched, over-stuffed, stiffened, wired, dyed and distorted, destroying their natural elegance and beauty. (19) Taking a close look at the yellow-bellied marmot donated by Charles R. Conner, Vertebrate Museum at Washington State University, in figures 9 and 10, one can see how, if improperly structured and staged, a preserved animal can appear awkward, forced, and stiff. Furthermore, its skin is visible through the fur and wrinkles in a way that would not appear in life.

Figure 9 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society exhibit

Figure 10 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society exhibit

To avoid this takes a sensitive touch and a delicate hand, as well as an understanding of each animal’s anatomy, attitudes, expressions, and environment. This feminine creativity is featured in figures 11 and 12, in which a mountain goat appears to be walking across boulders as it might have during its life. When staged in a landscape comparable to its natural habitat, a taxidermy piece can illicit a more organic state and effect for viewers. This specimen is courtesy of Pat Silvers, owner, and Bob Ulshafer, Sundance taxidermy specialist.

Figure 11 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society exhibit

Figure 12 Image Courtesy of Idaho Historical Society exhibit

Such a connection with nature is only the result of time and experience, putting the expert taxidermist on par with any great artist. Men and women alike offer uniquely special gifts to this field because it takes much more than the brute strength of a hunter to master it.

In fact, as opposed to brute strength, the process of preparing taxidermy pieces requires a keen eye for detail and a great deal of patience, aspects generally attributed to women. The following is an example of the process of taxidermy found in the Ladies’ Manual of Art written in 1890. The manual provides instructions for preserving animals, from monkeys to birds to reptiles and more. The following are historically accurate basic instructions that a woman during this time would have used to preserve a quadruped.

After the animals have been collected, the first step of taxidermy was to take comprehensive measurements of the specimen’s body. (20) Before starting the skinning process, one would plug the holes of the eyes, nose, and mouth to avoid staining the skin or fur with blood. (21) Next, using a knife one made an incision down the stomach of the animal and continued to carefully cut the skin from away from the muscle. (22) After the skin was removed from the torso, the head was detached from the body and its brain and eyes were taken out. (23) Once the skin had been taken off, the muscle and tendons were cut away from the bone. (24) After the bones had been thoroughly cleaned, one covered them and the skin with arsenical soap to preserve it. (25) The next step was to wrap the bones with tow or cotton, representing the natural shape of the muscle. (26) The skin was now pulled back over the bone and cotton. (27)

After pulling the skin back over the bone and cotton, the taxidermist would look over the skin to find any stains that must be removed using turpentine, careful to brush the fur or feathers in their natural direction. (28) Wire was then used to support the structure of the animal. (29) The wires were cut to reflect the measurements that were collected before the start of the skinning process. (30) The wire was inserted through the skin and attached to the bones. (31) Silver could be shaped to recreate larger muscles. (32) The body was then stuffed with chopped flax. (33) Next, the skin was sewn back together at the belly of the animal. (34) The face of the animal was then stuffed going through the opening of the eyes. (35) The eyes were then put back in and the mouth positioned. (36) The last step was to mount the animal and position it in the fashion desired by the taxidermist. (37)

Conclusion

As evidenced by the success of Maxwell, Vinnola, and Love, women as well as men have a knack for fixing the skin of animals over bones and other artificial surfaces to bring hunted game back to life. These women, and others, “have found the space afforded by the West [ . . . ] to expand into spheres considered the domain of men” (38), confronting gender norms by taking up practices generally associated with maleness and western masculinity.

______________________________

Footnotes:

1.”How Taxidermy Got Its Start,” Taxidermy Hobbyist: The Art of Taxidermy, accessed March 20, 2012, http://taxidermyhobbyist.com/history-of-taxidermy-got-its-start.html.

2. “How Taxidermy Got Its Start,” Taxidermy Hobbyist: The Art of Taxidermy, accessed March 20, 2012, http://taxidermyhobbyist.com/history-of-taxidermy-got-its-start.html.

3. Karen Jones, “Lady Wildcats and Wild Women: Hunting, Gender and the Politics of Show(wo)manship in the Nineteenth Century American West,” Nineteenth-Century Contexts: An Interdisciplinary Journal 34, no. 1

(2012), 37.

4. Jones, “Lady Wildcats and Wild Women,” 40.

5. Jones, “Lady Wildcats and Wild Women,”46.

6. “Did She Kill ‘Em All?: Martha Maxwell, Colorado Huntress,” National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum, accessed April 14, 2012, http://www.nationalcowboymuseum.org/research/cms/Exhibits DidSheKillEmAll/tabid/129/Default.aspx.

7. Jones, “Lady Wildcats and Wild Women,” 44.

8. “Did She Kill ‘Em All?”

9. “Women Hunters,” Women Hunters: For Women, About Women, By Women, accessed April 15 2012, http://www.womenhunters.com/.

10. Jane Keller and Dave Olsen, “Team Huntress: Empowering Women Outdo0rs,” Team Huntress, accessed April 15 2012, http://teamhuntress.info.

11. “How often have you said to yourself “I want to learn how to do taxidermy?”” Colorado Institute of Taxidermy Training, accessed April 15, 2012, http://www.coloradotaxidermyschool.com/.

12. Jane Keller and Dave Olsen, “Anne Vinnola,” Team Huntress, accessed April 15, 2012, http://teamhuntress.info/about/anne-vinnola/.

13. Jane Keller and Dave Olsen, “Anne Vinnola,” Team Huntress, accessed April 15, 2012, http://teamhuntress.info/about/anne-vinnola/.

14. Jane Keller and Dave Olsen, “Anne Vinnola,” Team Huntress, accessed April 15, 2012, http://teamhuntress.info/about/anne-vinnola/.

15. “Taxidermist Alicia Love wins ‘Best of Show’ at NWTF,” Women’s Outdoor News, accessed April 15, 2012, http://www.womensoutdoornews.com/2010/02/taxidermist-alicia-love-wins-best-of-show-at-nwtf/.

16. “Taxidermist Alicia Love wins ‘Best of Show’ at NWTF,” Women’s Outdoor News, accessed April 15, 2012, http://www.womensoutdoornews.com/2010/02/taxidermist-alicia-love-wins-best-of-show-at-nwtf/.

17. “Taxidermist Alicia Love wins ‘Best of Show’ at NWTF,” Women’s Outdoor News, accessed April 15, 2012, http://www.womensoutdoornews.com/2010/02/taxidermist-alicia-love-wins-best-of-show-at-nwtf/.

18. Charles Waterton, “On Preserving Birds for Cabinets of Natural History,” in Wanderings of South America, the North-West of the United States, and the Antilles, in the years 1812, 1816, 1820 & 1824 (London: Fellowes, 1879), 321, accessed April 4, 2012, http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015005073682.

19. Waterton, “On Preserving Birds,” 321.

20. M.A. Donohue, “Taxidermy: Skinning, Preparing, and Mounting the Mammilia or Quadrupeds,” in Ladies’ Manual of Art: Or Profits and Pastime. A Self Teacher in all Branches of Decorative Art, Embracing Every Variety of Painting and Drawing on China, Glass, Velvet, Canvas, and Wood. The Secret of all Glass Transparencies, Sketching from Nature, Pastel Crayon Drawing, Taxidermy, etc. (Chicago: Donohue, Henneberry, & Co., 1890), 205, accessed March 20, 2012, http://www.archive.org/stream/ladiesmanualart00chicgoog#page/n6/mode/2up.

21. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 203.

22. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 203.

23. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 204.

24. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 204.

25. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 204.

26. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 204.

27. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 204.

28. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 204.

29. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 205.

30. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 205.

31. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 206.

32. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 208

33. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 209.

34. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 209.

35. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 210.

36. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 210.

37. Donohue, “Taxidermy,” 210.

38. Jones, “Lady Wildcats and Wild Women,” 47.

______________________________

Bibliography

“Did She Kill ‘Em All?: Martha Maxwell, Colorado Huntress.” National Cowboy & Western Heritage Museum. Accessed April 14, 2012. http://www.nationalcowboymuseum.org/research/cms/ExhibitsDidSheKillEmAll/tabid/129/Default.aspx.

Donohue, M. A.. “Taxidermy: Skinning, Preparing, and Mounting the Mammilia or Quadruped.” In Ladies’ Manual of Art: Or Profits and Pastime. A Self Teacher in all Branches of Decorative Art, Embracing Every Variety of Painting and Drawing on China, Glass, Velvet, Canvas, and Wood. The Secret of all Glass Transparencies, Sketching from Nature, Pastel Crayon Drawing, Taxidermy, etc., 203-211. Chicago: Donohue, Henneberry, & Co., 1890. Accessed March 20, 2012, http://www.archive.org/stream/ladiesmanualart00chicgoog#page/n6/mode/2up.

“How often have you said to yourself “I want to learn how to do taxidermy?”” Colorado Institute of Taxidermy Training. Accessed April 15, 2012. http://www.coloradotaxidermyschool.com/.

“How Taxidermy Got Its Start.” Taxidermy Hobbyist: The Art of Taxidermy. Accessed March 20, 2012. http://taxidermyhobbyist.com/history-of-taxidermy-got-its-start.html.

Jones, Karen. “Lady Wildcats and Wild Women: Hunting, Gender and the Politics of Show(wo)manship in the Nineteenth Century American West.” Nineteenth-Century Contexts: An Interdisciplinary Journal 34, no. 1 (2012): 37-49.

Keller, Jane, and Dave Olsen. “Anne Vinnola.” Team Huntress. Accessed April 15, 2012. http://teamhuntress.info/about/anne-vinnola/.

——. “Team Huntress: Empowering Women Outdoors.” Team Huntress. Accessed April 15, 2012. http://teamhuntress.info/.

“Taxidermist Alicia Love wins ‘Best of Show’ at NWTF.” Women’s Outdoor News. Accessed April 15, 2012. http://www.womensoutdoornews.com/2010/02/taxidermist-alicia-love-wins-best-of-show-at-nwtf/.

Waterton, Charles. “On Preserving Birds for Cabinets of Natural History.” In Wanderings of South America,the North-West of the United States, and the Antilles, in the years 1812, 1816, 1820 & 1824, 324-341. London: Fellowes, 1879. Accessed April 4, 2012, http://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.39015005073682.

“Women Hunters.” Women Hunters: For Women, About Women, By Women. Accessed April 15 2012. http://www.womenhunters.com/.